Isaak Iselin in Hawaiʻi, 1807

Women and Men – Comment

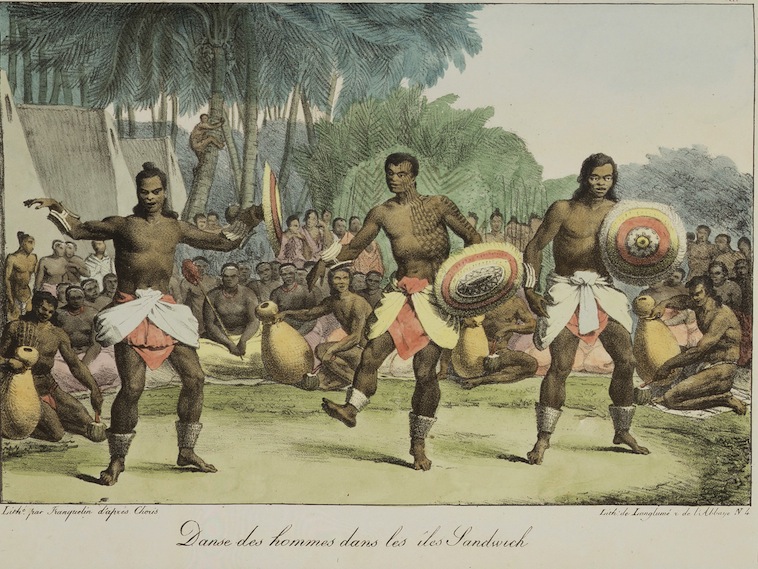

As a companion image to the dancing women at the beginning of this exercise, Choris also painted three dancing men. Choris, Louis. Voyage autour du monde, accompagné des descriptions par le baron Cuvier et A. de Chamisso; et d'observations sur les crânes humaines par le Docteur Gall. Paris: Didot, 1822, pl. 12.

As a companion image to the dancing women at the beginning of this exercise, Choris also painted three dancing men. Choris, Louis. Voyage autour du monde, accompagné des descriptions par le baron Cuvier et A. de Chamisso; et d'observations sur les crânes humaines par le Docteur Gall. Paris: Didot, 1822, pl. 12.

Die Transkription lautet:

«The females in these islands are obliged / during the time of their menses to retire from society to the woods / or some solitary place, and are for pain of death for both parties / prohibited all commuting with men during this time, an instance of it / is now exhibited by a lady that lived on board (M. Y.)* who has / retired to a rock above the watering place at Karakakoa, where / with a few attendants she stays under a shed of cocoanut leaves.»

*Ms. Young

«(…); it seems, we / shall have some female companions to Woahoo.»

«(…); in the / morning went on shore at the village on the westpoint / where I walked over the mountains to Karakakora bay / where I had a pleasant bath in the surf, surrounded by the / belles of the place.»

That Iselin writes about menstruation in the first extract is a rare example of openness in his journal. One explanation is that he considers John Young's Hawaiian wife from a self–perceived ethnographic, «scholarly» angle.

In the second passage, the Maryland takes on board female passengers from Kealakekua Bay to Oʻahu. In the absence of more detail, it seems strange that only women should have used the Maryland as a transport vessel. A possible explanation is that they came as the crewmen's companions.

The third scene, omitted of course in the published travelogue, is nothing short of astonishing. Iselin bathes with the «belles of the place»! From this scene we begin to sense some of the silences of the journal, particularly when it comes to Iselin himself. Did he have a female companion on board, for example? What was the nature of his (sexual) relationship(s) with Hawaiian women? And more generally, do these silences render Iselin an unreliable narrator of early–nineteenth century Hawaiʻi?

The Maryland with Isaak Iselin on board left Kauaʻi, the westernmost of the Hawaiian Islands, on July 19th 1807. His journal entries, letters to his brother and accounting materials are witnesses of the two months he spent on different islands of the archipelago. Through the lens of Iselin's perception a perspective on the Hawaiian Islands 1807 is gained; a Hawaiian–European contact zone is preserved in the Iselin family archive in Basel.