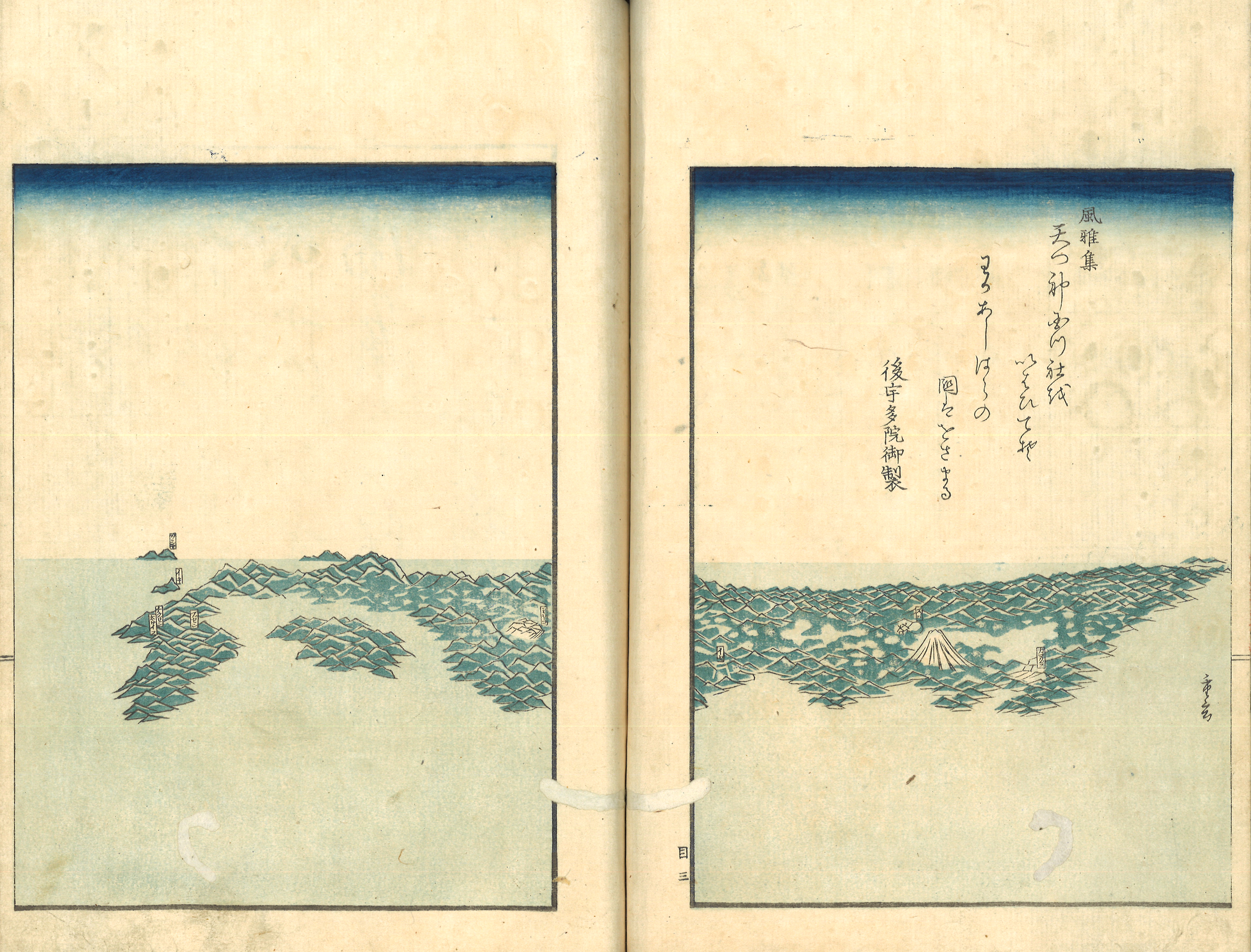

Bird’s eye-view of Japan, in Ishikawa Masumi, Mōzokuki, preface 1856 (Nagoya: Eirakuya Tōshirō, 1858), vol. 1; author's collection.

The text in the top right has it: ‘From the Fūgashū: the deities from heaven have hallowed the earth shrine, they rule over Japan, a poem by Emperor Gouda.’ (Fūgashū: amatsukami kunitsuyashiro wo ihahiteso, wakaashiharano kuniha wosamaru, Gouda-in gyosei).

Sugimoto Fumiko has coined the term ‘mapped society’ to characterize the Edo-period (1603–1868). According to Sugimoto, ‘[…] this period of Japan’s history has left us with a dizzying diversity of maps, each one made with particular goals in mind.’ Furthermore, Peter Kornicki has referred to the importance of maps within Edo-period print culture. According to him, commercially published maps functioned like books not only in terms of materiality, since they were folded to standard book formats and equipped with two covers, but because of the informations they presented:

[T]hey became for the Japanese reading public the primary means of envisioning spaces, from the city to the province, to the whole of Japan and even the world. These published maps testify to the spread of spatial literacy maps call for and to the increasing functional significance of maps in Tokugawa society.

Kornicki, Peter, The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century (Leiden, Boston and Köln: Brill, 1998), p. 60–61.

Finally, Mary Elizabeth Berry has indicated that maps were well available in the Edo-period ‘information library’. The latter term refers to Benedict Anderson's classical idea of print capitalism as a pre-condition to a shared sense of time and space that characterizes modern nations. A mid-nineteenth-century bird's eye-view of Japan reflects the spatial imaginaries circulated through maps. Recognizable are Japan's main islands, Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū. Three smaller islands, identified as Iki, Tsushima and Oki islands, are at the western horizon. To the east, Mount Fuji with a snow summit rises from the green relief-like design of the archipelago. The southern tip of Ezo (present-day Hokkaido) is visible to the north of Honshū. Yet, the shared notion of ‘Japan’, created by Edo-period maps, is still quite different from modern representations of the nation. This is suggested by the map genres, drawing and printing techniques and codes, which are presented in the following sections.